Written by Lauren Stanwicks and Pranita Atri

Highlights:

- Entrepreneurial academics are essential in bridging the gap between research and commercialization, playing a pivotal role in biotech innovation.

- Identifying these academics is crucial for investors, startup founders, and academic trainees seeking to collaborate or launch companies in a supportive environment.

- Metrics like leadership in startups, patents, SBIR/STTR grants, and clinical trials help in systematically identifying entrepreneurial academics.

- Top hubs include California and Massachusetts, with standout universities like Harvard, Stanford, UCSD, and UCSF.

In today’s landscape, more academics are bridging the gap between universities and startups, merging research with entrepreneurship. Identifying these entrepreneurial labs is essential not only for investors sourcing deals but also for academic trainees looking to build a startup with a supportive professor. Successfully founding a new venture requires more than just a novel scientific concept—it demands market insight and a commitment to translating discoveries into patient impact. Additionally, careers launched from a PhD onward greatly benefit from an awareness of labs, schools, and researchers who are business-minded.

At Nucleate, our mission is to provide open-access educational resources to academic trainees interested in biotechnology careers. Whether you aspire to launch a company, join a venture capital firm, work in business development at a pharmaceutical company, or pursue other roles, understanding entrepreneurial academics is key. By identifying and connecting these trailblazers with co-founders, investors, and the broader biotech community, we aim to support their journeys and provide guidance for your own. This overview on mapping entrepreneurial academics will help you navigate the world of biotechnology with greater clarity.

What Is An Entrepreneurial Academic?

“Entrepreneurial academics exhibit a spectrum of activities that demonstrate their commitment to translating research into commercial impact. They bridge academia and industry, shaping both scientific progress and commercial innovation.” - Arne Smolders, Founder & CEO of AcademicLabs

Defining an entrepreneurial academic is complex. In his article The Third Way: Becoming an Academic Entrepreneur, Javier Garcia-Martinez outlines three key factors for making the leap into entrepreneurship from academia: "solid research, a good idea about how to turn findings into a business opportunity, and a supportive environment." These academics possess a mindset geared towards translation and innovation, and they have the drive to start companies based on their research. According to Arne Smolders, Founder & CEO of AcademicLabs, “an entrepreneurial academic’s thinking is focused on producing and translating research into innovations that can be commercialized to scale impact on society.” In Understanding Entrepreneurial Academics - How They Perceive Their Environment Differently, Davey & Galan-Muros identify four main activities underlying academic entrepreneurship: (1) spin-off creation, (2) commercialization of R&D results, (3) joint R&D with industry, and (4) consulting, drawing on data from 10,836 academics across 33 European countries. The study found that entrepreneurial academics are most likely to engage in joint R&D with industry (16%) and consulting (12%), while commercialization of R&D and spin-off creation are less common (4%). Smolders emphasizes that entrepreneurial academics “exhibit a spectrum of activities that demonstrate their commitment to translating research into commercial impact,” including launching spin-offs, securing Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants, generating patents, and collaborating with industry through joint projects and clinical trials. While entrepreneurship is often defined as founding a company, considering these broader activities expands the definition of entrepreneurial academics and the scope of their contributions to both academia and industry.

Systematically identifying entrepreneurial academics presents its own challenges. Shelby Newsad addressed this challenge by manually scraping lab websites to compile her list of Top Entrepreneurial Bio Labs in the US, which specifically highlighted labs that have built companies or filed groundbreaking patents. "The Beaker List," curated by BIOS, recognizes the top 50 academic life science entrepreneurs in the U.S. who are shaping the future of medicine through venture-backed startups, patents, citations, and thought leadership in the TechBio field.

Here, we propose metrics to systematically identify entrepreneurial academics in the United States using open access resources in addition to the online resource AcademicLabs.com. While their defining characteristics may be broad, we suggest that entrepreneurial academics are likely to hold leadership positions in companies, have multiple patents, receive SBIR/STTR grants, and engage in clinical trials. Participating in entrepreneurial activities offers numerous benefits for academics, such as expanding their professional networks, accessing diverse funding sources, and bringing greater research impact. As Smolders explains, “most of all it opens up more paths,” providing not only career advancement but also intellectual growth and recognition, which can lead to sustained innovation and societal impact.

Academics in Leadership Positions of Companies

A commonly used metric for identifying entrepreneurial academics is their involvement in company formation and their ongoing roles in leadership or advisory capacities. AcademicLabs, an AI-powered life sciences discovery platform, enables comprehensive searches across early-stage research, spanning approximately 18 million experts, 150,000 labs, and 115,000 companies. In collaboration with AcademicLabs, we identified academics who hold the most leadership or advisory positions in companies and mapped the regions where they are most concentrated. We also analyzed the alma maters of recent founders.

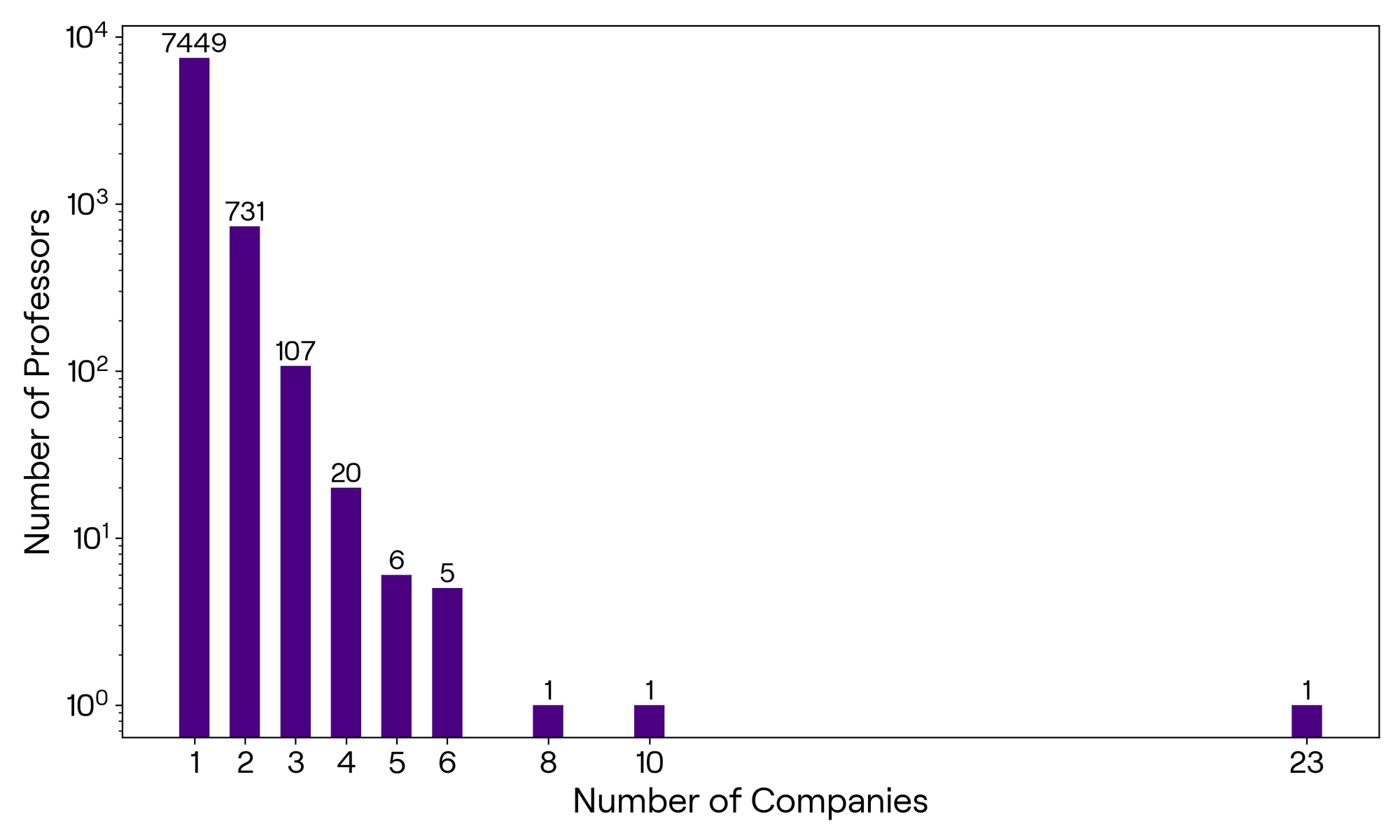

Our initial analysis focused on academics serving in advisory roles in companies founded over the past 10 years, with titles such as "Scientific Advisor," "Medical Advisor," "Clinical Advisor," or simply "Advisor." Unsurprisingly, renowned figures like George Church and Robert Langer topped the list (Table 1). Of the 8,332 companies founded in the last decade that listed an academic advisor, 89% of academics were listed only once, with most of these companies employing fewer than 50 people (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of the Number of Professors Listed as an Advisor for Companies In The Past Ten Years

When broken down by state, California led with 1,163 companies that had academic advisors, followed by Massachusetts with 1,125 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Academics in Advisory Positions of Companies By US State

We also analyzed the alma maters of biotech founders over the past decade, with the top five universities being Harvard, Stanford, UCSF, UCSD, and MIT (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Alma Maters of Leaders of Biotech Companies Founded in the Past 10 Years

Table 1. Top 20 Entrepreneurial Academics in Advisory Positions of Companies Founded in Past Ten Years by Number

| George M. Church | 23 | K. Dane Wittrup | 4 |

| Robert S. Langer | 10 | Aurélien Marabelle | 4 |

| Padmanee Sharma | 8 | Rob Knight | 4 |

| Lawrence Fong | 6 | Charles Cantor | 4 |

| Mark Davis | 6 | Jef Boeke | 4 |

| Beverly L. Davidson | 6 | Lori Kunkel | 4 |

| Eric Verdin | 6 | Arshad M. Khanani | 4 |

| Frank McCormick | 6 | Carl H. June | 4 |

| Randy Schekman | 5 | Pasi A. Jänne | 4 |

| Keith T. Flaherty | 5 | Howard Chang | 4 |

| Antoni Ribas | 5 | David Berry | 4 |

| Olivier Elemento | 5 | K. Christopher Garcia | 4 |

| Josep Tabernero | 5 | Bruce Korf | 4 |

| Guangping Gao | 5 | James P. Allison | 4 |

| Mark A. Kay | 4 | Tomi Sawyer | 4 |

| Frank Slack | 4 | Annalisa Jenkins | 4 |

| Robert Green | 4 | Scott Antonia | 4 |

Academics with Small Business Research Grants

SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) and STTR (Small Business Technology Transfer) grants are U.S. government programs that provide funding to small businesses for the development and commercialization of innovative technologies. SBIR focuses on supporting high-risk, high-reward research and development projects led by small businesses, while STTR encourages collaboration between small businesses and nonprofit research institutions to bridge the gap between basic science and commercialization.

For entrepreneurial academics, SBIR and STTR grants offer substantial advantages. These grants provide critical early-stage funding for research and development without diluting ownership or requiring repayment. By securing this support, academics can transform their innovative ideas into viable products or technologies, facilitating the transition from academic research to commercial ventures. Additionally, the prestige and validation associated with these programs can attract further investment and partnerships, increasing the chances of successful commercialization and broader impact.

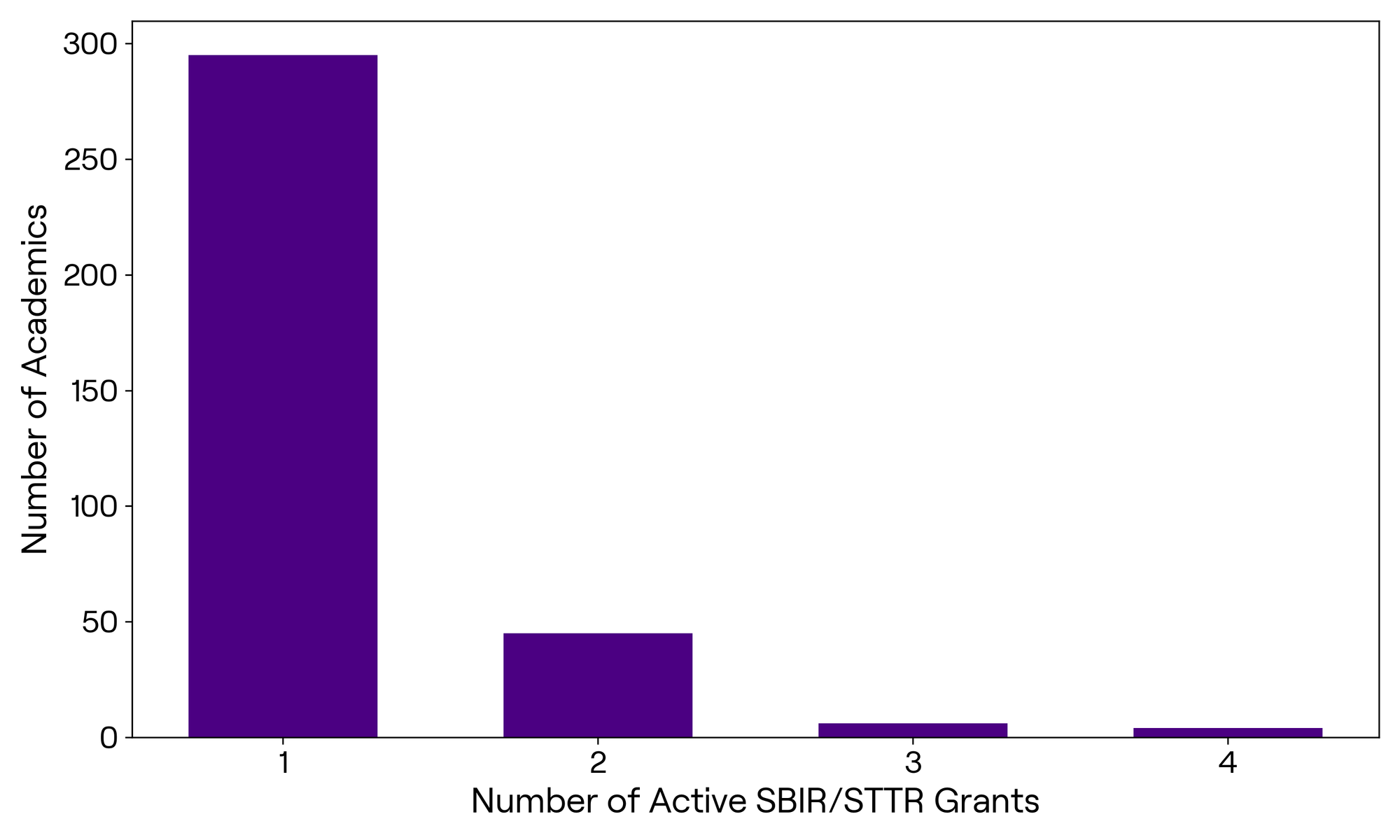

We used NIH RePORTER to identify the currently active research project grants awarded by the NIH. Among the 57,887 active academic research grants and 2,580 SBIR/STTR grants, we identified 350 academics who are principal investigators on both types of projects (Figure 4). These dual roles highlight their active involvement in both academia and industry, signaling a strong entrepreneurial presence. Remarkably, 84% of these academics hold just one SBIR/STTR grant, while four standout PIs—Erol Fikrig, Xiang Gao, Patrick Purdon, and Senthikumar Sadhasivam—lead the way with four active grants each (Table 2).

Table 2. Top Academic PIs With Most Small Business Research Grants

| Erol Fikrig | 4 | Xiang Gao | 4 |

| Patrick L. Purdon | 4 | Senthilkumar Sadhasivam | 4 |

| Francisco Jose Schopfer | 3 | Al-Hafeez Zahir Dhalla | 3 |

| Jian Zhang | 3 | Guoqiang Yu | 3 |

| Michael L. Shuler | 3 | Jian Kong | 3 |

Figure 4. Distribution of Academic PIs With Most Small Business Research Grants

Geographically, California tops the list with 47 professors across the state who hold both academic and small business research grants (Figure 5). However, when narrowing down to cities, Boston emerges as the clear leader with 20 dual-grant PIs, followed by Philadelphia and New York with 13 each (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Number of PIs by State

Figure 6. Geographic Heatmap of PIs by City

Surprisingly, the University of Pennsylvania is home to the highest number of dual-grant PIs, boasting 11 (Figure 7). This concentration could point to a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem within the institution, fostering collaboration where entrepreneurial PIs are often listed on each other’s grants.

Figure 7. Top 20 Academic Institutions with PIs that Hold Academic and Commercial Grants

Academics Leading Clinical Trials

By participating in clinical trials, universities contribute to advancing medical science, improve patient care, and enhance their research reputation while offering students and faculty opportunities for hands-on experience in translational research. We examined the universities that have conducted clinical trials within the past five years and found ~54,000 clinical trials across the United States with over 20,000 currently recruiting (Figure 8). Amongst these almost 50% (28,491) trials were sponsored by non-profit organizations like Universities, Hospitals, Institutes and Cancer Centers. In line with our expectations, the top 20 non-profit organizations included Cancer Center like M.D Anderson, Memorial Sloan Kettering as well as hospital networks including the Mass General Hospital network (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Number of Ongoing Clinical Trials By State

Figure 9. Top 20 Organizations with the Most Ongoing Clinical Trials

Entrepreneurial academics engage with clinical trials to validate the safety and efficacy of their innovative biomedical products or technologies in a real-world clinical setting. This validation is crucial for gaining regulatory approval, attracting investment, and building credibility within the scientific and medical communities. Clinical trials also provide valuable data that can refine and improve the product, ensuring it meets the needs of patients and healthcare providers. We examined individuals who have run clinical trials in the past 5 years while simultaneously holding an academic position (Table 3). The top 17 U.S. clinical trial investigators, as identified by AcademicLabs, can be accessed through this bookmarked link, allowing readers to explore their profiles and search options without the need to sign up.

Table 3. Entrepreneurial Academics Who Have Led The Most Clinical Trials in the Past 5 Years

| Gülay Altun Uğraş | Philip E. Bickler |

| Raul G Nogueira | Richard J. Bloomer |

| Timothy A. Yap | Madhav Thambisetty |

| David Hui | Arun Jayaraman |

| Warren K. Bickel | Momchilo Vuyisich |

| Zev Schuman-Olivier | John W. Apolzan |

| Christina M. Dieli-Conwright | Brian M. Ilfeld |

| Lan N. Vuong | David C. Nieman |

| Ajay Goel | Shivan J. Mehta |

Academic Patent Distribution

Universities and academics across the globe play a major role in creating patented technologies that beneficially impact society and enable the most innovative companies in the world. To showcase the important research and innovation taking place within academic institutions, the National Academy of Inventors ranks the top universities holding U.S. utility patents in both the US and the world (Figure 10). These include The University of California system, MIT, University of Texas system, and Purdue. While impressive, the number of patents could be a function of school size, as the University of California system has 10 campuses employing 25,400 academic staff, while MIT, for example, is a single campus employing 1,069 academic staff as of 2023.

Figure 10. Top 20 US Universities Holding U.S. Utility Patents, from https://academyofinventors.org/top-100-us-universities/

When examining the top academic patent holders through AcademicLabs, a clear overlap emerges between those with the most patents granted and those with the most patent applications in the past five years (Table 4). Many of these individuals are affiliated with leading research institutions that hold US patents, such as Jennifer Doudna at UC Berkeley, George Church at Harvard, Feng Zhang at MIT, Robert Langer at MIT, and Robert Cooks at Purdue. Notably, these prolific patent producers are also prominent in our metrics for top company advisors and leaders, highlighting their influence beyond academia.

Table 4. Top 20 Academic Inventors with Most Patent Applications and Patents Granted since 2019

| Patents Granted | Patent Applications | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| George M. Church | 110 | Jennifer A. Doudna | 206 |

| Robert S. Langer | 101 | Feng Zhang | 205 |

| Jennifer A. Doudna | 93 | James M. Wilson | 176 |

| Feng Zhang | 91 | George M. Church | 172 |

| Robert Cooks | 89 | Robert S. Langer | 158 |

| James M. Wilson | 66 | Robert Cooks | 137 |

| Irving L. Weissman | 58 | David R. Liu | 124 |

| David R. Liu | 56 | David Baker | 123 |

| Guangping Gao | 55 | Guangping Gao | 117 |

| Anant Madabhushi | 54 | Carl H. June | 115 |

| David A. Weitz | 52 | Anastasia Khvorova | 113 |

| Jian Li | 52 | Carlo Giovanni Traverso | 103 |

| John A. Rogers | 50 | Arsham Hatambeiki | 102 |

| Richard B. Kaner | 49 | Martin Jinek | 99 |

| Donald E. Ingber | 47 | Krzysztof Chylinski | 97 |

| Paul D. Arling | 44 | Emmanuelle Charpentier | 96 |

| Seyed Ali Hajimiri | 44 | Donald E. Ingber | 86 |

| Carl H. June | 43 | Irving L. Weissman | 81 |

| Mark A. Griswold | 43 | Paul D. Arling | 78 |

| Stephen R. Forrest | 43 | Anant Madabhushi | 77 |

How Best Is An Entrepreneurial Academic Identified?

So, where are entrepreneurial academics? Everywhere! The truth is, it depends on what you are looking for.

Academic entrepreneurship is viewed as a way for universities to create value from their knowledge, yet there remains ambiguity about what activities constitute academic entrepreneurship. Collaborating with entrepreneurial academics—whether during your PhD, as an early-stage founder, or in a biotech career—is highly valuable. The challenge, however, is identifying these individuals and the opportunities they represent. To address this, we analyzed various metrics within the AcademicLabs platform and beyond, seeking to provide practical solutions for locating entrepreneurial academics and unlocking their potential.

Arne Smolders notes that "a limited or non-existing industry network remains a critical barrier to academics intending to pursue industry partnerships, identify problems to solve, and understand the competitive landscape." This suggests that networking and collaboration opportunities are essential for academic entrepreneurs in addition to tools to connect with industry partners and stay updated on relevant innovations.

Interestingly, the four metrics we analyzed yielded distinct results in identifying the most prolific academics and the highest-ranking universities. There was little overlap between the top academics across each metric, except in advisory roles in companies and patents. However, universities and states showed more consistency, likely due to well-developed tech transfer offices or supportive university cultures. Classic biotech hubs like California and Massachusetts consistently ranked at the top across all metrics. Universities that performed well in one metric tended to appear near the top in others, with standout institutions including UCSF, UCSD, Harvard, Stanford, and the University of Pennsylvania.

Additionally, it appears that academics with a high volume of patents are often those involved in many spinoffs or company advisory roles. In contrast, academics engaged in many clinical trials or small business research grants represent a distinct group of entrepreneurial scientists. This suggests that entrepreneurial academics follow diverse paths, each contributing to innovation in different ways, whether through commercialization, industry partnerships, or clinical research.

Entrepreneurial Academics Beyond the United States

While this article focuses on academic entrepreneurship in the United States, the global landscape offers some interesting contrasts. Data from AcademicLabs reveals significant regional differences in how entrepreneurial academics engage with industry. For example, in the U.S., only 5% of academic advisors to companies are also the founders of those companies, whereas in Europe, this number is 60% higher, with 8% of advisors also acting as founders. This may suggest that in Europe, academic founders often remain involved as advisors throughout a company’s growth, whereas in the U.S., the most suitable advisor for each stage of development is sought externally.

In the US, top academic inventors tend to have a steady stream of filed and granted patents, with 2/3 of the researchers consistently appearing among both the top 20 recent patent filers and patent holders. By contrast, European top inventors typically have 2-3 times fewer patents, and less than half of the leading 20 inventors appear on both the lists for patents filed and patents granted. This difference suggests that European patent activity may be more concentrated around significant breakthroughs, leading to clusters of related patents, whereas US inventors pursue a more continuous and incremental patenting strategy, aligned with ongoing commercialization efforts.

A different trend emerges in clinical trials. India leads globally with 417 academic researchers involved in at least six clinical trials, nearly double that of the U.S. (225) and China (224). European countries like Germany are further down the list, with 93 researchers. This discrepancy could be explained by a higher proportion of investigator-led trials in countries like India and China, where only 15-25% of trials are industry-sponsored, compared to approximately 50% in the U.S., Europe, Japan, and South Korea. This suggests that in countries with fewer industry collaborations, academics may be more inclined to lead their own trials to address unmet medical needs. At the same time, it highlights the underdevelopment of industry-academia partnerships and entrepreneurial ecosystems in these regions, where researchers have fewer opportunities to collaborate with industry on clinical research.

Academic Entrepreneurship and You!

To thrive, academic entrepreneurs require a distinctive blend of skills. They must embody the characteristics of traditional scientists, such as dedication, meticulousness, and technical expertise. Simultaneously, they must have entrepreneurial traits, including the ability to identify business opportunities, create customer value, and take calculated risks. They must aspire to achieve ambitious goals while reliably fulfilling their commitments and critically evaluate which research projects are most likely to yield commercial success. Smolders notes, “a strong force is required to favor turning research into IP, which can be a risky path, instead of publications, which offer a guaranteed small win.” Without support from entities like Tech Transfer Offices or external organizations, many academics may find it difficult to move their research toward commercialization.

Academic entrepreneurs face several significant barriers. Research has shown that entrepreneurial academics are more often middle-aged men (Davey & Galan-Muros, 2020). This trend highlights not only the underrepresentation of women and minorities in positions of power in science but also the reality that middle-aged men may feel more secure in their careers, making them more willing to take on the personal and professional risks of academic entrepreneurship. A solid enabling ecosystem is vital to breaking through these barriers, as academic entrepreneurship often requires knowledge and resources outside of traditional academic environments.

Nevertheless, there are clear benefits to entrepreneurship for all academics. Engaging in entrepreneurial activities broadens professional networks, provides access to diverse funding sources, and can greatly enhance the impact of research. As Smolders suggests, “organizations like Nucleate are critical forces to empower academics in becoming more entrepreneurial.”, playing a crucial role in connecting academics with the right resources and networks, enabling them to scale their impact beyond academia. Additionally, the intersection of academia and industry offers valuable new perspectives and complementary skills. Spinning off your research forces you to think more broadly and creatively, solving technical challenges that might not arise in a traditional lab setting. The process sharpens your presentation and negotiation abilities while improving your capacity to manage teams and resources. This hands-on experience can unlock new opportunities, such as industry funding and collaborations, which can propel your academic career forward.

AcademicLabs

If you are curious about how AcademicLabs can benefit you, Nucleate is happy to provide you with a one week free access pass. Simply sign up here with this code: Nucleate-EA

Much of the data presented in this article was gathered in partnership with AcademicLabs. AcademicLabs' mission is to bring transparency to academic and industry research and eliminate barriers in transforming ideas into innovations. The platform allows users to quickly find experts, research labs, startups, incubators, investors, and more in the life sciences. It also keeps users up-to-date with the latest research, including patents, grants, clinical trials, and ongoing programs worldwide.

Entrepreneurial academics can use AcademicLabs to find advisors, industry partners, incubators, and investors, as well as map their competitive landscape and track cutting-edge research. It also helps early-stage entrepreneurs connect with regional biotech startups and new projects.

Hidden Layers Team

| Lead | Lauren Stanwicks |

| Team Members | Romina Horianski, Anisha Sharma, Ivy Fernandes, Pranita Atri, Samantha Fabregat |

| Graphic Design | Marley Rossa, Angela Li |

Data Sourcing

The information in this report is based on data and trends from NIH RePORTER, Clinical Trials.Gov, and AcademicLabs as of October 2024. Due to the dynamic nature of the biotech industry, some details may change following publication.

References

BIOS Community. (2022). BIOS Beaker List: Top 50 serial academic life science entrepreneurs. Medium. https://medium.com/bios-community/bios-beaker-list-top-50-serial-academic-life-science-entrepreneurs-bc605e2352fc

Davey, T., & Galan-Muros, V. (2020). Understanding entrepreneurial academics‐how they perceive their environment differently. Journal of Management Development, 39(5), 599-617.

Garcia-Martinez, J. (2014, March 20). The third way: Becoming an academic entrepreneur | science | AAAS. Science. https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2014/03/third-way-becoming-academic-entrepreneur

Shelby Newsad. (2022). Hummingbird Ventures notion page. https://hummingbirdventures.notion.site/c1d62c36a979442eb2ad585f97ef4339?v=159fab3c6e074256955a72d48f3c3fb4

National Academy of Inventors. (2023). 2023 top 100 worldwide universities announced by the National Academy of Inventors. https://academyofinventors.org/2023-top-100-worldwide-universities-announced-by-the-national-academy-of-inventors/

SBIR. (n.d.). About SBIR. https://www.sbir.gov/about